Caveon Speaks Out on IT Exam Security

By: Dennis Maynes

Former Chief Scientist at Caveon Test Security

Introduction

Over several years, Caveon’s independent and analytical position in the testing industry has given us the opportunity to review data from many major Information Technology (IT) certification programs. From our unique position, we have seen critical and pressing issues that all IT certification program managers should understand concerning the security of their exams. These are:

- Proxy test taking is big business

- Braindump usage continues to undermine IT certifications

- Test theft appears to be unchecked

- Technology greatly facilitates collusive test taking

- Stakeholder support must be won

In this paper, we share our perspectives on these issues. We hope this information will provide greater insight and ability to make decisions which will heighten the security of your exams and strengthen IT certifications as a whole. While many of these issues appear to be more problematic for IT certification programs than for other programs, we are concerned they may eventually affect all programs.

The Magnitude of the IT Exam Security Challenge

Investment losses due to test theft are incredibly high. In 2005, we saw an advertisement where a provider of test preparation materials offered to sell its entire inventory of brain dumped exams for $200. This seemed like a ridiculously small sum so we purchased the inventory. To our shock and amazement, we received exact word-for-word and pixel-for-pixel copies of over 500 live exams from more than 50 IT certification programs. While we do not have exact valuation numbers, we can use the industry-standard guideline that items cost1, on average, $300 to $500 to develop and publish, and therefore, exams with 60 questions cost $18,000 or more to produce. Thus, for $200 we purchased exam content that cost more than $9 million to produce!

We simply can’t keep up to the rate of security leaks. To create new items, do the proper psychometric work and republish exams costs us a fortune.

— Unidentified IT certification program manager, quoted in “ATP Exam security Council Security Initiative Survey Report,” June 18, 2007

The value of test integrity appears to be elusive. The reader may think that the above cited industry-standard costs of exam development are high. After all, many test questions are just a few sentences with a few answer options. “How expensive,” the reader might ask, “can it be to write just a few sentences with a small number of answer options?” The fact is that rigorous standards are strictly followed in the item development and test creation process. These standards ensure that tests are fair and valid, something which candidates and their prospective employers demand and desire. But the production of high-quality tests requires significant investment and care, which necessarily results in high item development costs. Virtually all candidates want to be treated fairly and will object when a test may appear to contain the tiniest of flaws. Yet, many have no qualms about gaining an unfair advantage over others and are curiously silent with respect to cheating and test theft.

For some exams, cheating is epidemic. Not only are exact copies of tests stolen, as we have verified; but, we have confirmed that many test takers embrace the purchase and use of stolen test content. In a carefully constructed analysis conducted in 2009, we found an astounding statistic with respect to braindump usage. Of 598 test takers on a very popular exam, we inferred statistically that more than 80% of them used braindump content. Even though the pass rate on the exam was 93%, we found that nearly all of the individuals who passed would have failed had they been graded using the carefully constructed non-scored items that were seeded into the exam. We estimated that only 7% of those who passed did so legitimately. Thus for this testing cohort, we believe that nearly all of the individuals who passed the exam were unqualified.

Revenues are impacted by braindump usage. In the analysis of the above exam, we were quite certain that over 500 individuals passed illicitly. The exam costs $125 to take. This means that the IT certification program lost over $60,000 in retake revenues as a result of the exam content being sold on the Internet. We admit this is hypothetical, because if the exam were administered securely most of the test takers would have studied, gained the requisite knowledge, and demonstrated competence; rather than resort to braindumps. But at a target pass rate of 60%, the program still lost $25,000 dollars in retake revenue in one month. That is roughly equivalent to the cost of producing the exam!

Test fraud hurts everyone, including cheaters. IT certification programs, along with their test development vendors, follow careful standards and guidelines to produce sound and valid tests. This takes time, effort and money. Yet, we have seen entire item banks stolen and sold within days or even hours of the exam’s publication. This sad state of affairs may be summarized as follows:

Items are costly to produce,

Valid tests require great expertise to construct,

Thieves steal test items quickly,

Cheaters buy and use them, and

A large number of awarded certifications are phony.

The net effects to the IT certification organization are that many individuals, who are supposed to be proficient, do not represent the certification that has been awarded to them, they undermine the integrity of the organization that certified them, they devalue the certification itself, and they may damage those who employ them through their ineptitude. These negative effects are felt by all, including those who received their certifications through illicit means.

Test fraud is a difficult and persistent problem. The total size of the IT certification market is very large. We estimate3 that at least 3,000,000 exams are administered yearly with registration revenues exceeding $300 million. Other statistics4 related to the size of the market are:

Over 100 IT organizations provide certifications,

– More than 1,500 braindump websites sell illicit content,

– Approximately 500 test preparation websites appear to be legitimate, and

– More than 200 companies provide classroom instruction.

These statistics show that there is great demand for IT certifications. Because a person’s job and status depend upon the certification, there are powerful incentives to cheat. In other words, these are high-stakes exams. Moreover, most of the illicit websites and organizations that are selling stolen content to braindump users are off-shore and beyond the reach of US law. Consequently, the current problems are not going to go away easily. Each IT certification program must take proactive steps to address test security issues.

Investment in security is good business. A central premise of our paper is that IT certification programs should invest in security solutions in order to protect test-development investments, the integrity of the industry, the trust of test takers, and the confidence of the public in certified IT specialists. Test security efforts make good economic sense. For example, if an investment of $10,000 in security is able to double the service life of an exam which costs $60,000 to produce, the net savings to the certification program is at least $50,000. Going beyond the savings in item-development expenditures, the overall quality of the products and services provided by certification vendors will be significantly enhanced; and not least, purchasers of these products and services will have a better overall experience because certified personnel can be relied upon to perform competently.

Proxy test taking is big business

Officials at Cisco and Pearson VUE told The Boston Globe this week that during an eight-month span ended in June 2008, they monitored hundreds of thousands of exams given in eight countries in Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North America. Cisco said it had confirmed that one in 200 of those exams [were] taken by a proxy, and not the actual enrollee.

— Kevin Baron and Alan Wirzbicki, July 22, 2008, “Study confirms widespread cheating on job exams”, Boston Globe

Proxy test takers are branching out. As a natural consequence of monitoring the Internet, we have seen in the past few years that proxy-test-taking services have broadened their outreach. Where previously only the largest IT certification programs were impacted, we now see these services being offered for many of the medium-sized and even some of the smaller IT certification programs. These organizations also appear to be spilling over from the IT sector into other certification and testing arenas.

Proxy-test-taking organizations are multinational. Response time statistics and pass rate trends are being used in the industry for detecting proxy-test-taking. At Caveon, we have augmented these approaches with advanced techniques, such as within-test-site clustering6, cross-site similarity matching7, and unsupervised differential item functioning8 (DIF). These combined methods are able to expose the scope, size, and strength of proxy-test-taking organizations. In our analysis performed in 2007, we first found two test sites being operated by proxy test takers. And then using these advanced techniques, we found they were operating five more test sites in several other countries. Thus, we learned that proxy-test-taking organizations often control or operate test sites, internationally.

Super-human performance is exhibited by proxy test takers. Proxy-test-taking organizations appear to employ individuals who specialize in specific exams. These specialists have the ability to memorize entire item banks and answer-keys. With near instant recall, they are able to pass tests by answering most of the questions in three seconds or less9. They, also, can immediately recognize when the exams have been republished. Many of them appear to be aware that statistics are being used to expose them, so they attempt to defeat simple detection methods by altering their behavior. For example, we have seen them let the computer remain idle for several minutes (e.g., 20 or 30 minutes) in order to lengthen the testing session time despite the rapid answering of test questions. In the meantime, they take another test on another workstation, working at an equally prodigious rate. Fortunately, our sophisticated and robust statistics are unaffected by these evasive maneuvers, and we are still able to detect and track these specialists.

Braindump usage continues to undermine IT certifications

Braindump usage can be detected. Despite efforts of many individuals to discourage the use of braindumps, a sizeable proportion of the test taking population relies upon braindumps of actual exam content to take the tests. Two recent developments for tracking pervasiveness of braindump usage are (1) Trojan Horse items and (2) score difference analysis between scored and non-scored items.

Trojan Horse items detect users of stolen answer-keys. A Trojan Horse (TH) item is an item that is non-scored and published with an incorrect answer-key. These items are able to reliably detect when an individual is using a stolen answer-key. Because answer-keys are encrypted and never displayed to test takers or site administrators, we believe answer-key theft is accomplished through the unauthorized decryption of exam content after it has been downloaded to test site servers. Depending upon the popularity and desirability of the certification, the prevalence of stolen answer-key usage may exceed 20% of the test-taking population.

EMC instituted Trojan Horse questions and monthly forensic review of all exam results over a year ago. We are now able to identify and take swift action against identified cheaters and others who threaten the integrity of the EMC Proven Professional Program. All EMC Proven Professionals, as well as their employers and customers, benefit from this robust test security program.

— Gene Radwin and Liz Burns, EMC Corporation, August 6, 2009

Statistics provides the foundation for Trojan Horse detection. With an appropriate number of TH items on the exam, it is possible to obtain strong probability evidence that an individual used a stolen answer-key while taking the test. The number of Trojan Horse (TH) items needed to reliably detect answer-key purchasers and to minimize the lengthening of the test by adding TH items is determined by statistical analysis. Because we desire to make a statistical judgment using the TH items, care is required in choosing the number and quality of the TH items. In general, our guidelines for selecting TH items require us to measure the statistical properties of the items and to make policy decisions concerning the desired detection parameters (i.e, probability thresholds and robustness against imperfect recall of the stolen answer-keys).

Inconsistent response patterns clue us in on braindump usage. Score differences between two subsets of the items on the test may reveal inconsistent response patterns. When the score differences are very large, the test taker is simultaneously displaying ignorance and knowledge. We presume that an unprepared test taker using braindump content will have a high score for the previously published items and a much lower score for the newly published items13. If we detect an extreme difference, we will infer that performance was not consistent on the test. Consequently, because the difference is positively associated with the items that have been in service for some time, it is reasonable to conclude that the inconsistent performance was the result of prior exposure to the exam content.

Proper statistical techniques require careful science

Throughout the industry, we have seen that the analysis of difference scores is often done improperly. For example, some programs assume that the two sub-test scores being differenced are independent and that standard statistical formulas are appropriate. This approach, however, underestimates the true variance and overstates the magnitude of the observed difference. Other programs use the standard error of measurement as the basis for standardizing the score difference. This approach ignores the fact that the standard error of measurement was computed from all the items, when the sub-test scores were not computed using all the items. It is nearly always the case that normality is assumed even when it is not appropriate.

At Caveon, we have developed exact statistical methods for computing the probability distribution of the difference score. These techniques do not assume normality, homogeneous variances, or independence. Instead, they use statistical distributions that naturally arise from the item response models.

Difference scores reveal more than 85% of all test takers may use braindumps, for some exams. Recently, we have analyzed three specific situations involving exams shortly after they were re-published with non-scored items. In these analyses, we measured a wide range of braindump usage (35%, 40%, and 85%). We have seen that score differences are able to reveal and discover individuals who are unqualified, but who are nevertheless passing the exams through the use of braindump content. For high-volume, high demand exams, we estimate that braindump usage may reach 85% or more of the test-taking population.

A few braindump users appear to be naïve. A certification program manager reported one candidate did not know that the “actual questions” offered by the braindump websites were, indeed, the live exam questions. He had supposed the statement was a marketing claim. After discovering his error, he voluntarily surrendered his certification and waited until a revised exam was ready in order to retest. This example illustrates the importance of countering the braindumps’ marketing messages with focused educational campaigns. The Certguard website is focused on helping test takers identify legitimate test preparation sources. Taking nothing away from Certguard’s efforts, we believe that all IT certification programs should provide positive messages and education that promote ethical test taking.

The newest addition to exam policies is that of classifying results as indeterminate. Basically based on data forensics, our security consultants identify suspicious results and depending on the strength of the data, say a 1 in 10,000,000,000 chance of a specific result occurring, I can definitely with confidence conclude that a result is not sound and will invalidate those results. Once invalidated, a result will not count toward certification.

After putting these policies and procedures in place it’s been really interesting what I have found:

Once people know someone is looking, they repent and cease with their misconduct.

Education of candidates is key; in fact candidates often state that they did NOT know that they were in violation of the NDA or any other policy.

Even those with the most grave violations, seem to value the cert when they are in danger of losing it.

— Sierra Hampton, Manager – Exam Development, Citrix, “Cheaters Beware,” August 8, 2008, Citrix Blog

Test theft appears to be unchecked

Test theft occurs at test centers. The high demand for stolen content by braindump purchasers means that efforts to steal exam content will continue. We have seen exact word-for-word and pixel-for-pixel reproductions of test items, including the minutiae that are inserted by the content editors. In fact, we have performed content editing for a few clients with the express purpose of detecting when and by whom the exam content was being stolen. Our research indicates that theft of IT certification exams occurs through the compromise of the encrypted exam data that are resident on local servers at test sites.

The major source of theft for IT certification exams is simply retrieving the downloaded files, and decrypting them if necessary. From the evidence gathered in my research on the content of braindump sites, the thieves have a proven “system” for capturing the questions.

— David Foster, Kryterion, December 8, 2007

Proactive steps can produce positive results. A few programs have discovered that specific patterns of exam registration and scheduling are strongly correlated with the appearance of stolen exam content on Internet braindump sites. Using this discovery, EMC successfully detected the test sites where their tests were being stolen, shut the test sites down, and thus deterred exam theft. When Caveon attempted to purchase the exam items from the thieves’ braindump site, the website administrator replied, “We cannot provide EMC exams to you. Every time we get them our ability to administer the tests is taken away.” (The website may have quit selling exams for the EMC certification program, but the last time we checked it was still selling content for other programs.)

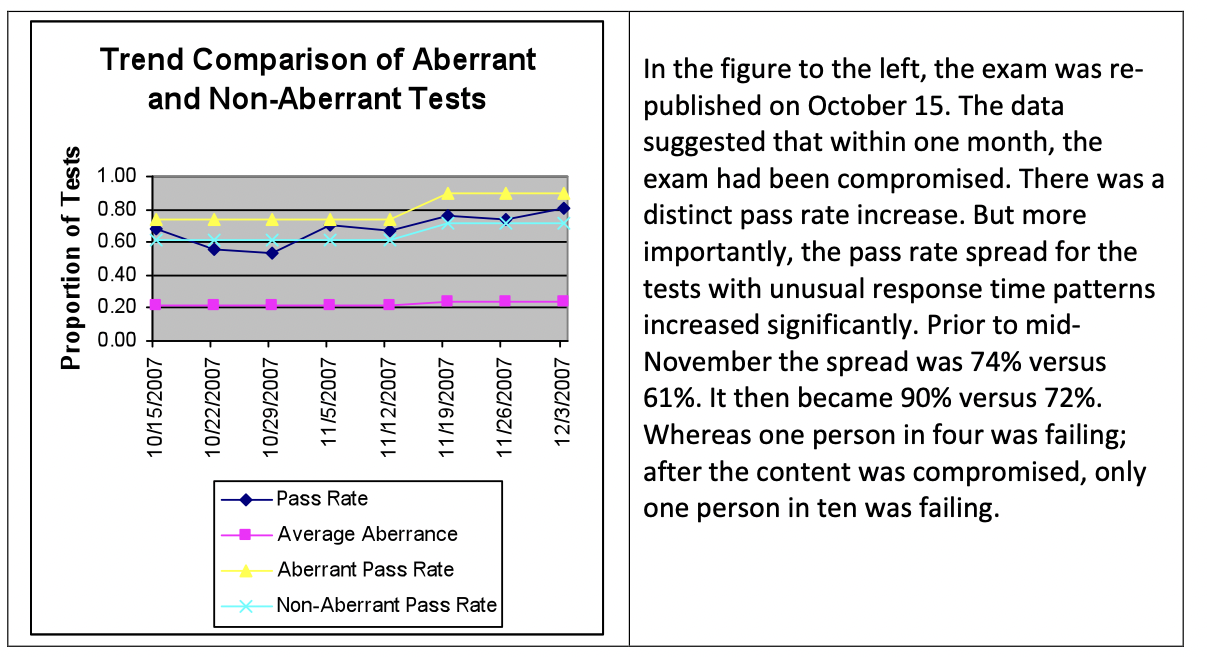

Tests can be stolen very, very quickly. While it may take time for some exams to be stolen, we have seen by using data forensics and Internet monitoring that exam content can be stolen and disseminated within days or hours of re-publication, once the test thieves are aware that the exam has been re-published. The thieves determine to steal the exams through (1) announced re-publication schedules and (2) “returns” by braindump purchasers when they are not able to pass the exams. Thus, high-demand exam titles are especially vulnerable to theft and a program manager must take steps, in addition to re-publication, to protect valuable exam content. A common misconception among IT certification program managers is that items become exposed gradually over time, through repeated administrations. We have learned this is generally not true. An event, such as the theft of the test, is nearly always responsible for the compromise of exam content. As an example of our findings, we refer the reader to Figure 1.

Figure 1: Pass Rate Changes That Illustrate Exam Compromise

A majority of the IT respondents (56%) reported that 45% or more of their exams have been stolen or compromised. Approximately 32% of the IT respondents believe that more than 60% of their current certification exam have been stolen or compromised. Approximately 24% of the IT respondents believe that between 46 and 60% of their certification exams have been stolen or compromised.

— ATP Exam security Council Security Initiative Survey Report, June 18, 2007

((There were 50 respondents to this question on the survey, with 22 non- respondents.))

The ignorance of test thieves can be used to strengthen IT exam security. We believe that the thieves’ ignorance about the testing program can be exploited to provide additional security to the testing program. For example, we have learned that some non-scored items of multi-form exams may never be stolen. This means that braindump usage may be estimated using these non-scored items. It also means that test centers frequented by braindump users may be detected. From a psychometric perspective, once it is possible to reliably detect the tests taken using braindump content, those tests can be set aside and reliable item statistics may be computed. After reliable psychometric models are created, those models can be used to determine which items (using DIF analysis on the discarded tests) are most heavily compromised. Knowing the compromised items means that the program manager needs to only replace the compromised items and not the entire item bank, which represents a potentially large cost savings. These techniques are possible because the thieves are unaware of the form structure of the exams. They only realize their stolen content is no longer viable when pass rates fall, and the purchasers of the stolen content request refunds because they were “guaranteed to pass.”

Many tools are available for dealing with test theft. In summary, test theft is accomplished very quickly in today’s IT certification environment. Exam re-publication is one tool at the program manager’s disposal for countering test theft. Other tools and techniques, however, are also very important and may be used to devalue the stolen content being distributed on braindump sites. One of the techniques discussed in this paper involved detection of theft followed by test site closures where the theft occurred. Other techniques such as Trojan Horse items and score difference analysis between scored and non-scored items can target braindump purchasers, directly, to revoke scores. Plus, we have developed other techniques that create cognitive confusion in the mind of the braindump user in order to impair the recall of memorized content. All of the techniques, just mentioned, for dealing with test theft are extra-legal. We do not believe that IT certification program managers should use litigation (which can be expensive, time consuming, and unfruitful) as their only means of dealing with test theft. We believe that IT certification managers have many options, without relying exclusively upon legal prosecution of braindump sites, to stem the tide of test theft.

Technology greatly facilitates collusive test taking

Many cheating devices are virtually undetectable. Gone are the days when two cheaters needed line-of-sight communication in order to collude. Cell phones and Internet-ready devices have guaranteed that wireless transmissions are the cheaters’ method of choice. Yes, it is true that all of the old methods are still used. But the old methods have been augmented by new cheating techniques and technologies. We have seen and talked to many testing organizations who stated emphatically, at first, that their test administrations were secure and then, later, after seeing the data forensics evidence were equally convinced that test takers were cheating.

Collusion can be detected using statistics. The very best statistic for detecting collaboration and collusion or “non-independent test taking” is the response similarity statistic. Unfortunately, this statistic has not been widely studied in the academic literature. We strongly recommend and urge every testing program to use response similarity statistics. They are capable of detecting the location and the perpetrators of collusion.

“There will always be cheating as long as there are tests,” Crowley noted. But Microsoft is using some high-tech methods to catch cheaters. The newest method is a data forensics program that identifies patterns indicative of cheating and piracy. “Unusual response times or ‘aberrant’ responses can indicate fraud,” Crowley says. “Any time you take a test you leave data behind,” Crowley says.

((Peggy Crowley is the anti-piracy program manager for the Microsoft Learning department))

— John Brodkin, July 9, 2008, “Microsoft cracks down on certification exam cheating,” Network World

Brief history of collusion and answer-copying statistics

Answer-copying statistics have been studied in the academic literature for some time, with the first being discussed as early as 1927. Most of this literature has focused on using incorrect identical answers as evidence of test fraud. Additionally, prior to the mid-1980’s and the wide-spread use of modern IRT methods, most techniques relied upon ad-hoc response probability estimation. Some researchers in the literature have been unwilling to use identical correct responses as evidence of answer-copying, because they view the use of identical correct answers as being difficult to defend as evidence of potential test fraud.

Many researchers have emphasized that identical answers, whether incorrect and correct, should all be utilized. These researchers have developed several variations of the response similarity statistic, which fundamentally test the hypothesis that two tests were answered independently. Bay’s method, published in 1995, was based on overall p-values and did not take into account the fact that response probabilities depend upon performance. Wesolowsky’s method, published in 2000, focused on a specific non-IRT based statistical methodology for estimating item response probabilities. In 2006, van der Linden and Sotaridona published a uni-dimensional similarity statistic with item response probabilities estimated using the nominal response model. We have found their work to be appealing and powerful because it uses formal hypothesis-testing methodology.

Just as van der Linden and Sotaridona did, we have adopted the nominal response model. But, we have accommodated the differential information inherent between correct and incorrect identical responses by using a bi-dimensional similarity statistic. This statistic returns probabilities 100 times smaller than van der Linden’s statistic when cheating is present.

Stakeholder support must be won

Internal obstacles hamper test security efforts. After interviewing a large number of IT certification program managers, we have learned that the number one challenge to strengthening IT exam security is not the lack of technology or tools; rather it is the inability to overcome resistance within the IT organization to taking action against cheaters. Most legal departments are reluctant to invalidate scores and to revoke certifications for individual test takers. Many partnering organizations are opposed to being the recipient of a test-site shutdown notice. These stakeholders create significant resistance when strengthened security measures are proposed.

Stakeholders must understand the true cost of test fraud. An educational program is needed to help these stakeholders understand the actual impact to the business when unqualified individuals are allowed to present themselves as being qualified, with the full backing of the certification program. Cheating rots the integrity of the certification program. Like all forms of rot, the effects may not be apparent until drastic measures are required to save the program. When this happens, the program manager may have very few options, short of dismantling the program and starting over. Even then, it may be too late to begin anew. Stakeholders need to understand this. One certification program manager remarked that the attorneys and partners need to become part of the solution and invested in the security process for this to happen; and once this is accomplished, test security can be greatly strengthened.

Although the number of individuals who pass their exams as a result of fraudulent exam prep or test taking behavior is very small, it can have a big impact on the value of your certification. EMC is committed to providing the highest level of exam security and does take action when fraudulent exam practices are uncovered. Every month we perform a statistical analysis of all exam result(s). Any exam results found to be questionable – with a high probability of being the result of exam fraud – we revoke. We have been doing this for over two years with great success.

— Liz Burns, EMC Proven Professional Program Manager, posted on the EMC Community Network, August 27, 2009

Once lost, the public trust is not easily restored. When cheating effects are not countered, the entire business may suffer. The sole purpose of IT certifications is to provide qualified personnel who can support the products and services which are the company’s core business. When qualified personnel are no longer available or when the company’s clients lose confidence in their ability to support the products and services, the company’s core business will suffer.

Credibility and integrity, backed by tests that are securely and fairly administered, are the hallmark of the IT certification program. Without them, the IT certification has no value.

The testing channel presents a dilemma

Insiders pose the greatest security risks. In the discussion above, we have named specific security threats that involve the testing channel. The operation of test centers by proxy-test- taking organizations and test pirates presents difficult challenges to the program manager. Additionally, the data suggest that employees at otherwise reputable testing locations may “look the other way” for a small consideration and allow a test taker to gain an unfair advantage (e.g., bring a friend, use a cell phone, or use an Internet-ready wireless device). It is critical to acknowledge that individuals who control the computers and facilities where tests are given are within the security-trust network. Such an individual is an “insider” and may easily breach the security of the exam. All it takes is a camera and a little ingenuity.

Not all forms of secure testing are equal. The certification program manager must choose wisely among test delivery options and third-parties who will be admitted into the security-trust network. Some testing vendors provide two-factor authentication17 in order to prevent proxy test taking. Others provide reviewable recordings of every testing session. And, others may install metal detectors and other elements of physical security. There are many choices. Ultimately, the program manager is best served by reducing, as much as possible, access that third-parties are granted to secure exam content. For example, test items are more vulnerable when they are distributed and stored on local servers than when they are fetched in a secure manner directly from the Internet. We have seen interesting technical developments in this area which merit serious consideration. To date, we have not seen 100% security in any set of administered exams. But, we have seen large differences in security risks and some solutions are more trustworthy than others. We are optimistic that technologies, such as Kryterion’s secure online testing which relies upon strong authentication and remote proctors, will offer increased security.

Progress in certifications security will not just be a matter of vigilance and improved candidate monitoring, but innovation in the areas of exam development and exam delivery. And it is great to learn that, in addition to our own exam development team, there are so many people working toward that goal.

— Cris Cohen, blogger for the Cisco Learning Network; written June 11, 2008 in “On Certification Security.”

Cheating at test sites is facilitated by the environment. Whenever we analyze test result data from IT certification programs, we always find that some testing areas have “hot” spots. The hot spots seem to differ from program to program, but, they are often located in the countries of India, China, Pakistan, and Korea. Sometimes the hot spots are located in Europe, Africa, the United States, and other countries. In other words, security risks are present all over the world, with the greatest being present in the Asia/Pacific region. We have specifically found that test sites operated by training organizations present unique security challenges. These test sites are often the home of boot camps, where pass guarantees are extended to attendees. We suspect that many boot camps steal and drill the exam content, without ever selling it on the Internet.

Trained people are essential for good IT exam security. Although this discussion has focused on technologies and to some degree test delivery models, we emphasize that effective security is only possible when trained and dedicated people use the security techniques properly. Technology, alone, does not provide security. Trained and dedicated personnel are essential in the quest to strengthen security. Individuals with malicious intent may always bypass any security measure, if they have access. In this context, we repeat security expert Bruce Schneier’s words: “Security is a process.”

Is there a way out?

The risks are real and very costly. The security risks that are faced by the IT certification programs are real. Cheaters and thieves are taking real dollars away from the certification programs. They undermine the value of the certifications and take dollars away from honest and ethical test takers. Finally, they erode the public trust in the goods and services that are produced by the IT companies and supported by “certified” individuals. Thus, we firmly believe that cheaters and thieves hurt everyone, including themselves.

We believe there is a way out. Given the conditions we have described, certification program managers face a daunting challenge. The most important decision that a certification program manager can make in this regard is to begin now, today, to take charge and deal with these issues. It will take consistent and dedicated action, but we have evidence that security can be improved, as has been accomplished by many of our clients. At Caveon, we believe the technology, the tools, and the knowledge are available for dealing effectively with each of these challenges.

We are ready and able to help. At Caveon, we believe we have many of the answers and solutions for these problems. We understand the industry and the nature of all IT exam security challenges. With our tools, we can measure the security risks that you face. We have developed techniques for communicating what needs to be done. We believe that these risks may be dealt with responsibly, when they are quantified, when they are understood, and when appropriate responses are implemented. We invite you to contact us. We look forward to helping you deal with these risks positively, proactively, and preemptively.

We stand ready to assist you in your mission to administer tests fairly, securely and with integrity.

— The Caveon Team

About the Author

Dennis Maynes, Chief Scientist, is a founder of Caveon Test Security. He has a distinctly unique way of examining data and statistical evidence, which he considers to be one of his strengths. His favorite question to ask in presentations is: “If you trust the test score, a statistic, to make life-changing decisions (such as awarding a certification), why do you not trust statistics from the same data to decide whether the test result is trustworthy?” He is a strong advocate of using data in a practical manner. He says, “If you don’t look at the data you won’t know what to do, because you can’t manage what you don’t measure.”

Dennis began development of Caveon Data ForensicsTM in February, 2003. Since Caveon began offering services to clients, the data forensics group under his direction has conducted more than 200 data forensics analyses for over 40 clients. Dennis says, “Every analysis is different and unique. Even when the same exam titles are being reviewed on a monthly basis, the specific situations and potential testing irregularities which we detect vary.” With this wide experience including analyses for the Departments of Education of ten states, for twelve different IT companies, six medical programs, and programs from government, military, admissions, professional, and human resources sectors, Dennis is uniquely placed to discuss security issues from industry-wide perspectives.

Dennis holds the degree of Master of Science from Brigham Young University in the discipline of Statistics. He has worked as a software engineer, an educational researcher, a machine-learning specialist, and not least, as a statistician. Dennis’ first introduction to Item Response Theory occurred at Wicat Education Institute in the early 1980’s. At that time, he developed systems for computerized adaptive testing and for automated test assembly. Since founding Caveon, Dennis’ research has focused on practical algorithms for cheating detection. These algorithms include fast evaluation of the nominal response model with limited sample sizes, exact probability density computations for similar test statistics, and approximations of statistical distributions for linear aberrance statistics. Efficient computations are very important because he has processed test results for more than 15 million test instances during the past six years.

Additional Resources

How Okta Won with Threat-based Security: A Case Study

The SmartItem™ on SailPoint Certification Exams

How Zendesk Used Training and Certification to Promote Inclusion

“AI Item Writer” Wins 2024 Innovation Award

Exam Security Unlocked: Lockdown Browsers

The History, Evolution, & Future of Multiple Choice Tests

The Past, Present, and Future of Proctoring

The Language of Security and Test Security

What Is Computerized Adaptive Testing (CAT)?

READY TO TALK TO AN IT EXAM SECURITY EXPERT?

Reach out and tell us about your organization’s needs today!